The Inimitable Life and Death of Joe Cosley

If you were to approach a gathering of true, die-hard Glacier-philes and demand of the party a single pick for the most important person in the Park’s history, you’d likely be met with a squabble or at the very least a lack of consensus. Perhaps the “discovery and protection” orientated among the group would declare for the sainted George Bird Grinnel, while others might point out that the Blackfeet and other native tribes have existed here for over 12,000 years. Another faction could reasonably chime in for Louis Hill, the great promoter of the Park in hopes of profits for his railroad and hotels. Surely there would be a vote or two for the renowned naturalist, Morton J. Elrod. The hiking and climbing crowd might split in twain over the original exploits of Norman Clyde versus the instructional bent of J. Gordon Edwards.

Ask a more pointed query to that same savvy group, one invoking the search for the most colorful character in the history of Glacier Park, and the results are immediately reduced to a single, fascinating figure: Joe Cosley, the Panther-on-Snow-Shoes.

Park Ranger Joe Cosley poses in uniform for an official park service portrait in 1912.

NPS Archive Photo.

Joseph Clarence Causley (he later changed the spelling) was born on the Seven Nations Reserve in Ontario to a French-Canadian father and an Indian mother described alternately as Algonquin, Ojibwa, Cree, and Spanish. The genetic combination was referred to at the time as “Métis”, or more offensively as half-breed. Joe himself was often referred to as Oneida, and was once listed somewhat oddly as “an Irish Breed about three quarters Irish.”

Although Joe claimed his father was descended from Spanish nobility (odd but not unheard of for a Frenchman); his occupation is commonly listed as fisherman, farmer, and trapper. Cosley attended school with his 10-12 siblings at the Shingwauk Residential School from the ages of 8-11,and was then called Sahgahnuhquudo or “Cloud Appearing”. No record of his education is available other than suggestions that he received additional instruction at various convents, but his poetic writing and oratory skills reveal at least some form of continued learning which led Cosley to be described as “college-bred”. One paper listed him as graduate of the Carlisle Indian School, but as with much of Joe’s life, there is little that can be corroborated.

Joe Cosley portrait featuring his modified Glacier Park Ranger Uniform, 1910. I don’t think all the rangers painted red roses on the undersides of their hats! NPS Archive Photo.

Joe left home at the ripe age of 17, reportedly headed to Arizona before wandering the west and making his way north to punch cows in Montana. He made it to Kalispell (or more likely Demersville) in time for the big party celebrating Montana’s entry into the Union as the 41st state in late1889. Cosley made quite an impression on the denizens of the north county, and was described by Albertan rancher Bud Spencer as “tall, dark, and handsome; as agile as the mountain lion and with eyes twinkling with the freedom of the mountain stream.” A local paper detailed the appearance of the man known as “The Wild Horse Buckaroo” as including “a long black forelock, and a goatee that would make a mountain goat ‘go way back and sit down.’”

It is likely that Cosley assisted Lt. George Ahern and his attachment of “Buffalo Soldiers” in making the first trail and stock passage over the pass that now bears Ahern’s name. If you ever have the opportunity to visit Ahern Pass, you will almost certainly marvel at the incredibly rugged and steep terrain and wonder how anyone could possibly motivate a large string of pack horses to navigate the dangerous climb. It is rarely attempted on foot and often regarded as the most dangerous trail in Glacier Park, “fit only for a crazy man.” Ahern Pass later became Cosley’s preferred method of crossing the Continental Divide, although it was noted after a trip over in1912 that both the horse he was riding and his pack horse broke through a snow covered ledge and plummeted hundreds of feet to their deaths. Joe barely survived, but managed to later recover his fancy faux-alligator skin saddle and some of his supplies. It wouldn’t be his last adventure in the snow on Ahern.

Cosley shows off his artistic side with one of many drawings featuring “Bucking Broncs.” Tom O’Phileard was a cowboy buddy described by Cosley as one of the three “slickest horsemen in the Yellow Stone country” along with Joe himself, of course.

Joe soon set himself up as a fur trapper, maintaining trap lines stretching up to 200 miles that he monitored completely on his own, mostly around the Belly River Country connecting Glacier and Waterton Parks but also in the North Fork Country on the west side of the divide. He helped guide explorations for oil in the Belly for the “Belly River Oil and Development Company” in the early 1900s. Cosley’s incredibly long and swift adventures in the snow led to the Blackfeet nicknaming him “Panther-on-Snow-Shoes”.

A quick update on Cosley’s visit to Columbia Falls in The Columbian.

He was his own best booster, writing letters detailing his exploits (possibly including his new and possibly self-applied Blackfeet name) to every newspaper within 100 miles and checking in at each circulation’s office whenever he happened to be in town. The newspapers never had to go to Joe, according to Fred Burton, the publisher of the Cardston news in the early 1900s. Burton complained that the trapper always asked for payment in exchange for his tales of adventure, but the paper was far too small to afford paying for news- so Joe settled for the notoriety. Other publications did shell out rewards for Cosley’s articles, such as the multi-part and scintillating “Is Fighting Among Three Different Animal Breeds Possible?” He even managed to turn accidentally shooting himself in the shoulder in 1903 while fetching his mail into an excuse to self-promote his recent work in “the large eastern magazines and publications” where his “drawings are now frequently seen, having been largely copied. Mr. Cosley just finished a series of drawings for the Philadelphia Evening Post.” Joe’s stories may have outrun his experience from time to time, as he once described trapping in Northern Canada…when he hadn’t been there yet.

A typically “Joe Cosley is in town” notice from March 31, 1910- there are dozens of updates in the Columbia Falls papers during Joe’s time near Glacier. He was particularly prompt on updating the public if his mailing address happened to change.

The first superintendent of Glacier Park, William Logan, arrived in 1910 and set about assembling the original collection of Park Rangers tasked with protecting the pristine area from poachers and the like. Of course, Joe was a very well known poacher himself by this time (as were most of his fellow rangers) but Logan figured that intimacy with the geography of the park was vital and that “It takes a poacher to catch a poacher.” Cosley was assigned to the Belly River Valley…and kept right on poaching. He continued to use Ahern Pass to slip back and forth across the divide to run multiple trap lines, and was caught poaching near Lake McDonald within a year. He apparently completely ignored his firing, went back to work in the Belly, and somehow kept getting paid his Ranger salary! Don’t act like you’re not impressed.

Cosley’s original Belly River Ranger Station. Photo Kurt Wilson.

Cosley was fond of naming the natural features around his territory. The ridge and lake that now carry the name Cosley were of course named eponomously, but misspelled on maps and in literature for decades as “Crossley” before finally being corrected to the present, accurate form in the late 1950s. For the early rangers, the Belly River was simply referred to as “Joe’s”, “because there was only one Joe.” He quite famously named the many lakes in the Belly after his special lady friends, most of whom were the daughters and sisters of ranchers around Cardston, Mountain View, and Babb (then graced with the lovely sobriquet of “Main, Montana”). I first heard of Joe Cosley back around 2002 when I was cooking up fried chicken at Johnson’s of St. Mary, and I was told that all the names referred to Joe’s favorite Canadian prostitutes, which may have some truth to it, but none that I can verify.

Joe probably named Elizabeth Lake for his #1 lady, Elizabeth Webster of Mountain View, but he reportedly told anyone named anything close to Liz that he named it just for her. He also claimed to have named the lake after one of Teddy Roosevelt’s daughters…neither of whom was named Elizabeth. Sue Lake was named for Sue Henkel of “Main"; her relation George Henkel was one of the first rangers in 1911 and their family still ranches the area and the current generation owns the “Cattle Baron Supper Club” in downtown Babb. Cosley convinced two different women that Helen Lake was named for them while later confiding to another ranger that “both were a little cooler than Elizabeth.” The ranger wasn’t exactly sure how to take that statement. Another version goes that he named the lakes as he did because “Sue was the coldest. Elizabeth his best. He wasn’t talking about the temperature of the lakes.” Cosley told ranchers in the area that he named Cosley Lake after himself because it “ran endlessly deep just like he did and there was no way anyone could fathom its lavish wonders.”

The quiet shores of Cosley Lake. Photo Sanford Stone.

Cosley refused to stop poaching and he was eventually fired for real and for good in 1914. Taciturn Ranger Ralph Thayer was dispatched to deliver the news of the Buckaroo’s discharge from employment along with a personal message that the poacher aught to be ashamed for his actions after swearing to protect the wildlife in the park. Thayer’s dismissal of Cosley reportedly concluded with his admonition that “If I ever catch you on the trails in this park again, I will kill you.”

Joe apparently wanted to give the Germans a crack at that task, so he skipped across the border to Canada and became the first volunteer in the area to join the Cardston Troop of the Fort Gary Horse Overseas Mounted Rifles at the start of the Great War. “J.C. Cosley” as he was often referred to in print, turned out to be a pretty great war correspondent and wrote several detailed, poetic accounts of his experiences in the trenches (and burying a comrade) and “Sniping on the Western Front” (Cosley much preferred "sharpshooting” to “sniping” and bragged that his classification of First Class Marksman and Sniper may be high praise for a target shooter, but it was “little enough for a Rocky Mountain hunter.”)

The Cardston Mounted Rifles; Joe is in the center of the second row. Glenbow Archives.

Cosley was erroneously reported killed in action around 1917 after being just one of twelve men (out of 150) to survive a horrendous charge, in addition to being “the only one of the company to return on his own horse.” After over four years of service he returned to his beloved Belly River and made sure to announce in the local paper that he had shaken hands with both King George and Queen Mary. Cosley later elaborated that the king discovered his kill count of over 500 Germans and subsequently sent him home with “a pocketful of medals.” Other reports credit the crack shot with over 60 or 100 kills- whatever the number, there is little denying that the mountain man was skilled with a rifle in his hands.

In addition to his often fancy garb and saddles, Joe was known to carry this pearl handled .32 Winchester Revolver, which he later gave to a longtime Flathead County Commissioner. Cosley Exhibit in Cardston, AB.

Cosley’s return to the Belly River coincided with the uptick of tourism in the park after World War I, and the completion of the lodges and roads around the Park. He continued to trap and report his every adventure to the papers. The Park Saddle Horse Company (from which Park Cabin Co takes its name) helped create a system of tent camps and chalets one day’s ride from each other from their headquarters at Duck Lake (the current location of PCC). One of the main attractions of the riding circuit was the camp at beautiful then-Crossley Lake. The man himself would visit the tent city and engage wealthier tourists lined up to meet him and to see the park “Cosley Style.” Joe wrote letters to the Noffsingers, owners of the Park Saddle Horse Company, offering his unique talents to benefit their trips and repeatedly implored them to retain his services to provide tours of “Cosley Cave” which was said to be full of ancient petroglyphs. He wasn’t hired, so he must have asked for too much money…or the Noffsingers knew that the cave didn’t exist.

Unfortunately the magnificent mountainous backdrop is obscured in this 1920 photo of what was then called Crossley Lake Tent Camp, just east of the current Cosley Campsite. Photo R.E. Marble.

Cosley continued to trap, poach, and guide within Glacier and Waterton Parks until 1929, at which point his personal slogan of “Better Born Lucky Than Rich” may have turned on him. Ranger Joe Heims laid in wait for the wily poet-scoundrel and managed to arrest him in possession of his traps and furs. The story of their struggle varies a bit depending on the teller, with the feds referring to Cosley as “over 6 feet and 180lbs” while Heims was described as “five feet six inches and 145 pounds.” That report didn’t mention that the arrestee was a couple weeks shy of his 59th birthday while Heims was only 24. The feds also didn’t seem to mind that Heims actually ambushed Cosley two miles north of the Canadian border, which seems like a bit of a jurisdictional sticking point for a park ranger.

Cosley looking dapper as usual in this undated photo from the July 25, 1954 issue of the Great Falls Tribune.

In any case, Heimes waited just outside Cosley’s camp with his rifle and trusty Malamute until the old, larger-than-life poacher finally returned late in the evening. Cosley quickly detected the ranger’s presence and automatically reached for his rifle, prompting Heimes to declare that “If you put your hand on that gun I’ll shoot you right through the guts.” Cosley initially tried out a fake name, but eventually admitted that “Yes, I’m Joe Cosley all right, but there is no ranger in the park taking me in.” After a standoff lasting the entire night and featuring an unceasing stream-of-consciouness from the detained poacher, Cosley related that “he loved Belly River because it was so beautiful and untouched in lakes and streams and valley but the best part was that Head Quarters people never came there.” Heimes agreed entirely with his points, having similar opinions of “Head Quarters people.” By morning light, the young ranger had smoked all his cigarettes and announced it was time to start transporting the prisoner to HQ. Cosley repeatedly attempted escape from Heimes, even after the ranger “bumped his head up against a tree and sort of knocked him coo-coo.”

Cosley looking sharp in his Ranger duds.. Glenbow Archives.

Finally subdued, Heimes and another ranger transported his beligerant charge over Gable Pass on snowshoes and down to Slide Lake on the Blackfeet Reservation, where he was met by a government-issue Model T. If you’ve ever been to Slide Lake, you’ve seen what’s left of the “road” that travels from the Reservation boundary to the old park cabin at the lake. I hope it was in better shape for that trip via Model T. The threesome made it to Midvale (now East Glacier Park Village), and hopped on the train to Belton (now West Glacier). The local paper was naturally there to get Cosley’s photo. Joe was fined and jailed and Heimes finally got some rest.

Cosley was a “picturesque figure. Wearing a colorful neckerchief and earrings, there was a certain glamor about the young mountain man with a haunting face, Not too much was known of him: “Undated Portrait of Joseph CLarence Cosley, Great Falls Tribune photo and text.

It turned out that several of Joe’s friends in the area, prominent citizens all, had bailed Joe out of jail as soon as Heimes was out of sight. They managed to secure Cosley’s packsack, supply him with gear and grub and a new pair of snowshoes (the conspirators owned the Belton Mercantile, of course), and whisk him away to McDonald Creek an hour after his trial. By the time Heimes found out the situation, Cosley was on his way over Ahern Pass to the Belly River to retrieve his cache of illegally harvested furs. The disgruntled younger ranger knew that there was no way he could catch up to the “Panther-on-Snow-Shoes” and his long strides over the very dangerous pass in early May. So he hopped back on the train and reversed his earlier course back to the camp where he’d caught Joe red handed just a few days before. Heimes’s return to the site revealed that Cosley had already come and gone and “all tracks had been carefully erased and everything completely disappeared.” Pretty good snowshoeing. Later accounts of the events surrounding the arrest were greatly exaggerated by Cosley to include tales of Heimes stabbing him repeatedly with a Bowie knife, beating him with a bullwhip, and dragging him behind a horse all the way to Belton. Heimes refuted the stories thusly: “I have never seen a Bowie knife or a bull whip except in the movies.”

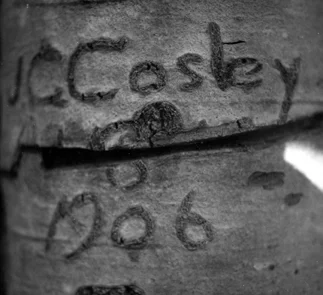

Detail of a “Cosley Tree” Great Falls Tribune

A more romantic version. Kurt Wilson Photo.

Our man Joe spent the remainder of his days in Canada, never returning to Glacier Park. He’d left plenty of evidence of his time there, marking hundreds of trees in the Belly River country with his name and the date. Legend has it (a legend that he went to considerable lengths to self-promote in the local papers) that Cosley purchased a $1500 diamond ring in Paris for his one true love (or one of them, anyways). His love cruelly spurned him and in his anguish he struck one of his many signed trees with an axe, creating a cleft in which he hid the diamond. He advertised far and wide that the ring was still out there, waiting for just the right finder-keeper. Others speculate that the series of events never happened, but if they had Cosley surely returned during one of his many seasonal spells of being broke and retrieved the ring for a grubstake.

Cosley continued to update his devoted fan club on his latest adventures in search of muskrat pelts.. Great Falls Tribune, March 29, 1926

Joe did continue to roam and trap in the Waterton area, but his adventures increasingly led him further north, into the far reaches of Alberta and Saskatchewan. His friends around Cardston and Mountain View relished his visits and continued to spread the amazing-and-probably-true stories of the man’s incredible ability to run or snow show 70 miles in a day just to attend a dance or speak to a pretty young woman. Cosley’s love of barn dances is still legendary here near Babb and in southern Alberta. Friendly with the ranching families on both sides of the border, he was always welcomed in for a meal and a chat about the news of the day. He was persistently described as a snappy dresser, but every report of his camps and cabins reveal that he lived in absolute and abject filth when not “in town.” His amiable companionship, beautiful prose, and many artistic endeavors seem at odds with his life as a “mountain man who loved seclusion and the isolation and vastness of these towering Rockies” as described by his friends. Towards the end of his adventures, the draw to that solitary existence appears to have taken a greater hold on Cosley.

News of Cosley’s demise published in the Great Falls Tribune on November 26, 1944.

If you’ve stuck with the story this long, I trust that you’ll agree with the first premise of the article’s title: Joe Cosley led a unique and fascinating life in the wilds of Glacier and Waterton. Well, his death was pretty amazing, too.

The old trapper finally made some concessions to his age and deteriorating condition by hiring a plane to take him and his equipment into the remote Saskatchewan wilderness of his final camps. Upon his ultimate departure to the far north at the age of 73, he remarked for the first and only time “If I’m not back in May, send someone to look for me.” When Mounties finally checked on Cosley two years later, he had been dead for a year. His diary reveals his battle with scurvy and the “cursed” cabin that he believed to be murdering him.

The following is Julia Nelson’s account of Joe’s painful end. I can’t top it, so here are her words relating the Mounties’ grisly discovery: “They found that Joe Clarence Cosley had dramatized his own miserable death as fully and effectively as he had his 74 years of vibrant, enthusiastic living.”

“The last of his hundreds of stories had plot, suspense and a gripping climax. In the diary lying near his bones he had not written 'I am dying of scurvy,' He told instead of a sinister curse, creeping and deadly, visited by some unknown power upon this lovely house. The trapper before him had died here, from the curse, of course, and daily Joe outlined his own suffering: 'I am steadily growing weaker...I can hardly write...I have reached the end...' He was conscious to the last, of the interesting pathos of the situation.”

“It wasn't a sad and regrettable ending. Anyone who ever knew Joe Cosley would tell you he wanted it that way.”

Cosley’s prose evokes a near-perfect spring day on the Rocky Mountain Front.

This blog was compiled using the following sources:

Belly River’s Famous Joe Cosley by Brian McClung

The Legend of Joe Cosley, Flathead Beacon

Joe Cosley: Glacier’s Infamous Belly River Ranger by Glacier Gazette

The archives of the Great Falls Tribune, The Columbian, The Choteau Acantha, and The Hardin Tribune-Heraldn

Joe Cosley Exhibit in Cardston, AB