The Drowned Town of Altyn

In a previous dispatch titled “In Appreciation of Mt. Wynn”, I briefly teased the tale of the drowned town of Altyn, currently slumbering in its sandy grave at the base of Mt. Wynn and Mt. Allen in the area known as Cracker Flats. It’s hard to imagine now that the pristine Many Glacier Valley was once home to a bustling, rowdy mining town- but indeed the windswept shores of the now-flooded Sherburne Lakes were the site of quite a population boom in the early 1900s.

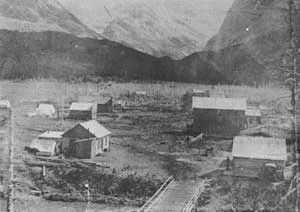

A post-boom Altyn on Cracker Flats as photographed by WT Stanton for the USGS in 1911.

The shores of Sherburne Reservoir are pretty quiet in the early spring before the seasonal melt water starts to flow back into the valley,

One feature that has remained constant is the condition of the road going into the valley- if you’ve driven it in the last decade or so then you know what I’m talking about! According to the Dupuyer Acantha, the road was just as bad around the turn of the century: “The road up to Swift Current in its present condition has been known to make a preacher curse, and I have my opinion of the man who makes the trip over this road (!) without breaking the 3rd commandment or perhaps all ten of them.” It sounds like the Park Service is actually going to rip up the asphalt from the dam to the entrance station and replace it with gravel in the next few years. Those of us at the Park Cabin Company are looking forward to that plan coming to fruition!

Town of Altyn 1888-1902, Glacier Park Archives

Many Glacier and the surrounding areas on the east side of the soon-to-be Park were first opened to mining settlement after the exchange of the still-contested “Ceded Strip” from the Blackfeet Tribe to the US Government in 1896. Two years later, the Swiftcurrent Valley was crawling with prospectors trying to stake a claim to riches in copper ore. One such pair of entrepreneurs traced a lead up Canyon Creek to a lovely spot then known as Blue Lake and stashed a cache of crackers and cheese at the base of Mt. Siyeh. Referring later to the “lead where we left our crackers” led to the christening of the Cracker Jack Mine, and later to applying the name to Cracker Lake as well. That’s the story, anyways!

A stalwart hiker poses at Cracker Lake, very near the location of the Cracker Jack Mine. Photo Credit to Howard Stone.

Hopes were so high for the Cracker Jack and Bullshead Mine on the shoulder of Mt. Wilbur that the exploration activity for the two combined under the “Michigan and Montana Company” and was capitalized at a figure of $300,000- worth nearly $9 million in 2019. Amazingly, a 16,000 pound ore concentrator was hauled from “Fort” Browning to Cracker Lake- first on a 12-mule wagon and then block and tackled up Canyon Creek. It took 29 days and even having seen the remains of the giant machine with my own eyes, I don’t understand how they got it up there. The contractor, Charles Nielson of Browning, was paid the princely sum of $25 per day for the transportation gig. The miners set up the steam-operated monstrosity on site…and never found enough ore to use it. They did manage to dig the mine out to a length of at least 1,300 feet. Entry is prohibited by the park service, so don’t even think about it!

To support the flurry of (astoundingly unsuccessful) mining exploration, a boomtown sprang into being in the area now known as “Cracker Flats” and was quickly named for one of the main financial backers of the mines- David Greenwood Altyn. The ramshackle mountain town reached its peak between 1899 and 1902 with a population nearing 800 people. (Babb and St. Mary combined can’t boast 800 people as I’m typing this in the winter months of 2019). Altyn boasted a post office, a general store, multiple saloons, a hotel, and even a newspaper office surrounded by the cabins and tents that served as homes for the miners. In its only known published issue, Altyn’s Swift Current Courier boasted headlines reading “The Growth of Altyn Assured “ and “No Doubt About The Permanency Of The Swift Current Mines.”

You may have noticed a low brick wall off in a field on your way to the Many Glacier Hotel. This is actually the gravesite of a woman who died in the town of Altyn. This photo is from 1924, when the Apikuni meadows were fenced and Bar X Six horses grazed the valley floor between trips into the park. These same horses likely roamed the current site of the Park Cabin Company, the former home of the Bar X Six ranch.

Unfortunately for the starry-eyed mineral seekers, no gold, silver, copper or any other ore was ever found in quantities that would justify further efforts mining the area. Most of the claims were abandoned, although a few were worked for some time and even patented to private ownership. A few of these rights remain in the hands of individuals, but most have reverted to the federal government. The Cracker Lake and Bullshead Mines were finally purchased in 1953 by the Glacier Natural History Association from Glacier County for the price of $123.96- the total to acquire the claims and turn them over to the park service.

A family of bears searches for springtime grub on the shores of Sherburne Reservoir, April 2005.

Just as the mining boom began to tail off (sorry), the Swiftcurrent Valley experienced another high-stakes endeavor with the discovery of oil. The owner of the two-story hotel in downtown Altyn, Sam Somes, discovered oil seepage while dynamiting out one of his claims near the present site of Sherburne Dam. Somes took a bottle of the oil to Great Falls and was met with much interest in his discovery. By the time he headed back to Altyn, Somes was the general manager of the newly founded Swiftcurrent Oil Company with financial backing of $1,500,000 (about $43 million in 2019).

Somes and others bought up nearly all of the Swiftcurrent Valley floor for oil placer claims, and proceeded to drill. The wells were not productive, despite reaching 1,500 feet into the ground. To drum up further interest, the story goes that Somes visited Great Falls and poured out jugs of his oil on the desks and floors of all the banks and offices in town. Despite the interest and considerable effort, the wells were mostly abandoned save for a few owned by local drillers like Mike Cassidy, who kept hoping to strike it rich. Cassidy kept his moderately productive well running until 1909, at which point he piped the gas to his house and used it for heating and lighting for several years. I would love to have seen Mr. Cassidy’s homestead!

A pair of callow young mountaineers encourage you to “Rock On” while following the long, long ridge from Mt. Wynn to Mt. Siyeh in the distance. Cracker Lake peaks up at the base of Siyeh in the middle of the photo.

Although very little oil was actually produced in the Valley, the area was awarded a diploma for “best display of crude and refined oil” at the State Fair in 1905. Rumors ran rampant that barrels of crude were actually imported and dumped in the well to trick investors, but it was never proven. Just like the mining boom, the oil boom was quickly busted. Those miners, oilmen, and rangers that continued to live in the valley eventually sold or traded their land to the government to make way for the new reservoir to be backed up behind Sherburne Dam. I hope to detail the construction of Sherburne Dam and the St. Mary Canal in a future long-winded post! The flooding of the valley in 1921 has erased nearly all remnants of the former settlements save for a few bits of Altyn’s foundations up on Cracker Flats.

So the next time you’re gazing across the usually-whitecapped waters of Sherburne Reservoir, give a thought to one heck of a frontier town- the short lived mountain metropolis of Altyn.

For more information, check out the following resources

Through the Years in Glacier Park: An Administrative History

http://mtmemory.org/digital/collection/p16013coll56/id/94/

https://malcolmsroundtable.com/2010/04/16/glacier-centennial-altyn-a-mining-boom-town/

http://hikinginglacier.blogspot.com/2012/01/cracker-lake-mine.html

https://www.trekearth.com/gallery/North_America/United_States/West/Montana/Glacier_National_Park/photo701924.htm

https://roamingbearmedia.com/2018/06/23/cracker-lake/